They call it controversial. They call it a problem play. They call it outdated, silly, absurd, farcical, a battle of the sexes and more. Most often, They call it a comedy and a romantic one at that. Some go so far as to call it the love story of a couple sure to be the happiest in all of Shakespeare-Land. Others call it sexist, misogynist, disgusting, demeaning or demoralizing. We may also hear difficult, complicated, nuanced or layered. In all of that, the one thing They don’t call it is… Tragedy. If They did, They could see that all the rest no longer applies or becomes irrelevant.

If we call The Taming of the Shrew Tragedy, we can also call it what it truly is: groundbreaking feminism ahead of its time, gut wrenching, frightening and sad. So very, very sad. For any who may be unfamiliar, this play by William Shakespeare is the story of Katherina Minola, aka The Shrew. The whole village wants to marry her younger sister Bianca, but their father insists older sister Katherina must be wed first. Uninterested in marriage, she is “so curst and shrewd” no man will take her, prompting Bianca’s suitors to find one who will. They pay the “mad-brain rudesby” Petruchio, who only wants a wealthy wife, to “wed her, bed her and rid the house of her.” Katherine gets no say in the matter whatsoever. “Forced to give my hand opposed against my heart,” Katherine is carried away by her new husband without even getting to enjoy her own bridal dinner. And since no one, not even the man who married her, can accept the feminist Katherina for who she is, Petruchio must now “tame” her into obedience and submission. Taming techniques include, but are not limited to: starvation, sleep deprivation and gaslighting.

This is the tale of a woman who is turned from a free-thinking independent spirit into a docile and subservient battered wife, bound to a lifetime without any free will or freedom. Using psychological emotionally abusive manipulation, animal training principles and the kind of sleep and food deprivation cult leaders also love to employ, Petruchio succeeds in his taming mission. Katherina is profoundly changed. She began the play as a person who vowed that she would always freely speak her own mind to the bitter end. She ends the play as a shell of her former self who now parrots Petruchio’s words and follows her master’s orders like a good dog. How could that be anything BUT a tragedy?

Still, for centuries They have insisted it is a comedy and a love story. This “Taming” mythos became the culture and the way of life. Aside from religious books of dogma, The Taming of the Shrew is arguably the most influential work throughout the last 400 years to permeate popular thinking about how a woman/wife is expected to behave, being “bound to serve, love and obey.” Girls don’t get to speak up, and they’d better not if they want to be liked by a boy. “A woman moved is like a fountain troubled; muddy, ill-seeming, thick, bereft of beauty. And while it is so, none so dry or thirsty will deign to sip or touch one drop of it.” Translation: “An outspoken, opinionated woman is dirty, annoying, fat and ugly. Not even the loneliest, horniest jerk will stoop so low as to be with her.” This is one of many messages that The Taming of the Shrew has ingrained so deeply into our culture that we simply accept it as the norm and never question it. Never questioning it allowed the Taming Culture of Old to thrive and evolve into the Rape Culture of Today.

How do we confront and combat rape culture head on? How can we make meaningful change? What if we start with The Taming of the Shrew? The mere concept that a woman must be “tamed” to be attractive and accepted as a proper wife implies male dominance, control and physical force. When Katherine asks the heartbreaking question in her final speech, “Why are our bodies soft and weak and smooth, unapt to toil and trouble in the world…?” these words sound to me like the sobs of someone who has been subdued by force. She tried to fight back. She tried to say no. Her voice and her will were completely ignored. She was not physically strong enough to stop any of it. She was allowed no choice whatsoever about when or to whom she would be married. Being forced into a wedding against her will, means she will also be forced into the marriage bed. She is legally obligated to submit to her husband’s desires, regardless of her own. Consent is not a consideration. Confronting rape culture means calling out the state and church sanctioned rape that not only happened in Elizabethan days but continues today all over the world throughout a wide range of cultures and religions.

Forced marriage and child brides are all around us. The stats and stories are too numerous to list them all but here’s one statistic from UNICEF USA, “According to data collected from 41 states, more than 200,000 minors were married in the U.S. between 2000 and 2015.” Want more? The non-profit group Too Young To Wed states that every two seconds a girl is married against her will. In the time it takes to read this sentence at least one forced marriage has occurred. Need more still? Simply Google “forced marriage” for an overload of horrific stories of domestic abuse, marital rape and church sponsored coverups. Forced marriage is not a relic of a bygone era. It is our world. It is now. Today.

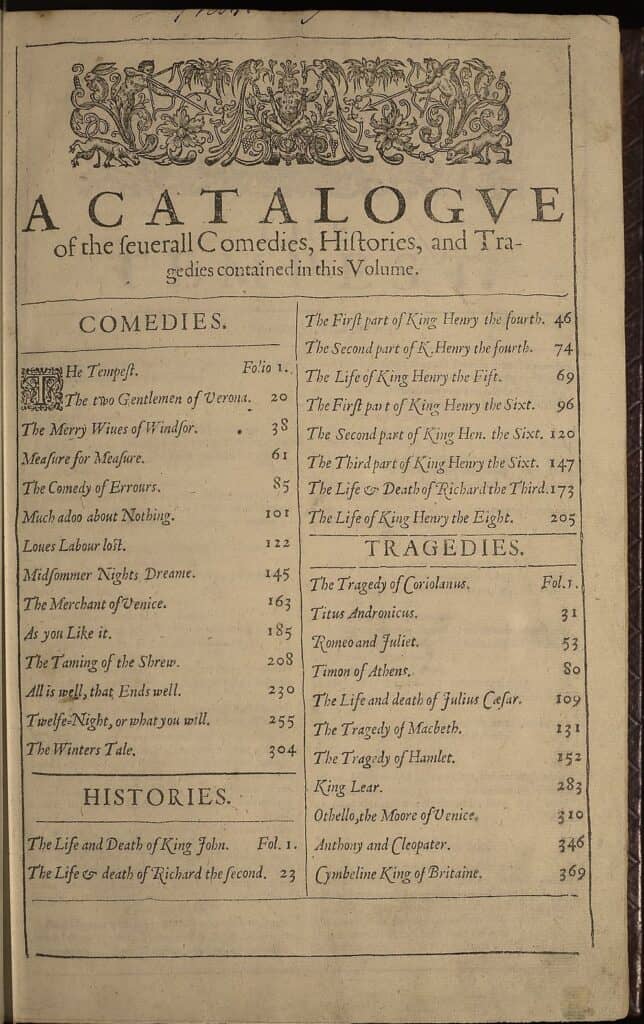

Clearly, forced marriage is a tragic event. So, why is The Taming of the Shrewstill produced and taught as a comedy? The Shrew we know today was included in the 1623 publishing of the “First Folio,” a collection of 36 plays ascribed to the playwright known as William Shakespeare, released seven years after his documented death in 1616. Many believe that these masterpieces might have been lost forever without the work of Shakespeare’s friends and fellow actors, John Heminge and Henry Condell, who compiled and categorized the First Folio. The term folio refers to the printing method used, folding one long page into four sections to create eight pages. The actual complete title of this publication is “Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories and Tragedies. Published According to the True Originall Copies.”{sic}

This catalogue demarcates each play into one of the three categories, Comedy, History or Tragedy. As far as we know, the actual playwright may have had nothing to do with these labels. The Shrew is not the only one on the comedies list to be rife with drama, dysfunction, abuse and oppression, however. The search for humor in The Merchant of Venice, for one, is like reaching into a basket of anti-semitic snakes. You won’t find a kitten, and if you do, it’s already dead. The Merchant and The Shrew have both been deemed “problem plays” for good reason. Aside from addressing a societal issue or problem, they are both seen as problematic within that assigned genre category of “Comedy.” They don’t quite fit the genre we think of today. They are not “funny.” Within the First Folio categorization, they share only one common element with the other “comedies.”

This catalogue demarcates each play into one of the three categories, Comedy, History or Tragedy. As far as we know, the actual playwright may have had nothing to do with these labels. The Shrew is not the only one on the comedies list to be rife with drama, dysfunction, abuse and oppression, however. The search for humor in The Merchant of Venice, for one, is like reaching into a basket of anti-semitic snakes. You won’t find a kitten, and if you do, it’s already dead. The Merchant and The Shrew have both been deemed “problem plays” for good reason. Aside from addressing a societal issue or problem, they are both seen as problematic within that assigned genre category of “Comedy.” They don’t quite fit the genre we think of today. They are not “funny.” Within the First Folio categorization, they share only one common element with the other “comedies.”

No one dies.

That’s it. No one, especially not the protagonist or title character, physically dies onstage.

When exactly death = tragedy became the E=mc2 of Shakespeare Theatre Theory is impossible for me to pinpoint at this time. The present-day prevailing school of thought being taught, however, is that when it comes to Shakespeare: if someone dies at the end it’s Tragedy; if people get married at the end, it’s Comedy. A little simplistic and dismissive of Shakespeare’s actual depth if you ask me. No one asked me. That’s why I’m telling you.

The Shrew fell out of favor for a couple hundred years after Shakespeare’s death in the 1600s but regained popularity in the 19th and 20th centuries. It is now more popular than ever, even as the general consensus continues to acknowledge there’s an “ick factor” in attempting to make forced marriage funny. Perhaps some of the insistence on romantic comedy comes from this “the hero must die” checklist perpetuated throughout academia for the past century. The misconception that tragedy requires death was certainly supported and possibly solidified in the 1904 book of lectures, Shakespearean Tragedy by A.C. Bradley. Bradley insists that to qualify in the specific expression of Tragedy known as “Shakespearean,” a play is,

“ …pre-eminently the story of one person, the ‘hero’, or at most of two, the ‘hero’ and ‘heroine’. Moreover, it is only in the love tragedies, Romeo and Julietand Antony and Cleopatra that the heroine is as much the centre of the action as the hero. The rest, including Macbeth, are single stars. So that, having noticed the peculiarity of these two dramas, we may henceforth, for the sake of brevity, ignore it, and may speak of the tragic story as being concerned with one person.”

In other words, “We choose to ignore the women. Only men are allowed in the ‘tragic hero’ club.” Bradley goes on with,

“The story, next, leads up to, and includes the death {[sic] his emphasis} of the hero. On the one hand (whatever may be true of tragedy elsewhere) no play at the end of which the hero remains alive is, in the full Shakespearean sense, a tragedy; and we no longer class Troilus and Cressida or Cymbeline as such, as did the editors of the Folio.[1] On the other hand, the story depicts also the troubled part of the hero’s life which precedes and leads up to his death; and an instantaneous death occurring by ‘accident’ in the midst of prosperity would not suffice for it. It is, in fact, essentially a tale of suffering and calamity conducting to death.”

Look at that. If Mr. Bradley can remove plays from the Tragedies list, then we can certainly add one. If he can dismiss “whatever may be true of tragedy elsewhere,” then we can revive and reexamine it. Aristotle’s Poetics , composed circa 330 BCE, was the first known theatre criticism. It analyzed this emerging art form and the genre of Tragedy. Nowhere in Aristotle’s analysis is death required for a circumstance or play to be tragic. He does give several other specific elements that must be present in a tragedy. I can pinpoint how and where The Shrew meets each and every one of them. (Future posts will deep dive into all of the specifics, stay tuned!)

Aristotle saw that while murder and suicide are indeed horrifically tragic, there are, in fact, fates worse than death. Bradley chose to ignore Aristotle, but did Shakespeare? Tranio gives a shout out to the great Greek in Act 1, Scene 1, which means Billy was certainly familiar with the ancient philosophers when The Shrew was penned. Although pinning down the exact date and chronology of completion is near impossible, we do know that The Shrew was one of Shakespeare’s earliest works. Later plays are generally considered more refined and sophisticated, fitting nicely in their prescribed genre boxes. But what if? What if the younger playwright were a little more experimental, pushing boundaries and drawing outside the lines? We know from his own words in this play that he was fully aware of “Aristotle’s cheques.” What if he used that knowledge to question the world around him? The Bradley perception of comedy revolving around marriage matches comes somewhat from the pattern established by the complete works as a whole. With The Shrew being the first of its kind, there is no pre-established pattern, therefore, it should not have to be confined to that little box. Perhaps, young William Shakespeare didn’t want to see Katherina, and all women, confined either? Maybe, just maybe, this great and unparalleled playwright, wrote something outside the box.

Nonetheless, even if we accept Bradley’s death decree, we can just as easily argue that Katherine’s body may survive the play but her spirit does not. What is the physical body compared to the psyche, the heart, the soul? No one physically dies at the end of The Shrew. Psychically, however? Psychologically? Someone definitely gets killed. Emotionally devastated. Spiritually eviscerated. Katherine’s soul is obliterated. She becomes a shell of her former self. Death might be a sweet release for Katherine, opposed to the life sentence of oppression and abuse she is sentenced to endure. At least Hamlet’s sorrows end with his final curtain. When Katherine’s curtain goes down, her suffering has just begun. It is essential that we start giving Katherine a second curtain call and start telling the truth of her story. Maybe then, we can end a little of our own suffering.

[1]Note: Troilus and Cressida was almost left out of the First Folio, added to later copies as a leaf insert at some point after the initial printing and is therefore not listed on the ‘Catalogue” page of categorizations.